The Book That’s Going to Change How You Cook Isn’t a Cookbook

It’s a fun, irreverent introduction to a science-based way of thinking about food and flavor.

I feel guilty that I’ve been slow to tell you about Flavorama: A Guide to Unlocking the Art and Science of Flavor, by Arielle Johnson.

I bought a copy on the book’s release date a little over a month ago. It has taken me that long to read through it: It’s so packed with useful info that I find I can digest only a few pages at a time before needing to take a break. Not because it’s textbook-dense or dry (my usual reasons for taking a long time to get through a book), but because there are so many valuable and often mind-blowing bits of information—ideas that challenge long-held assumptions or cause me to look at food and flavor entirely differently—that I frequently found myself thinking, Okay, that just upended what I thought I knew; I need to sit with this for a while.

The book also contains so much information, of so many different types, that it’s taken me that long to figure out how to describe it. The wildly oversimplified summary I’ve arrived at is this:

“This is why delicious things are delicious, and this is how to make them even more delicious.”

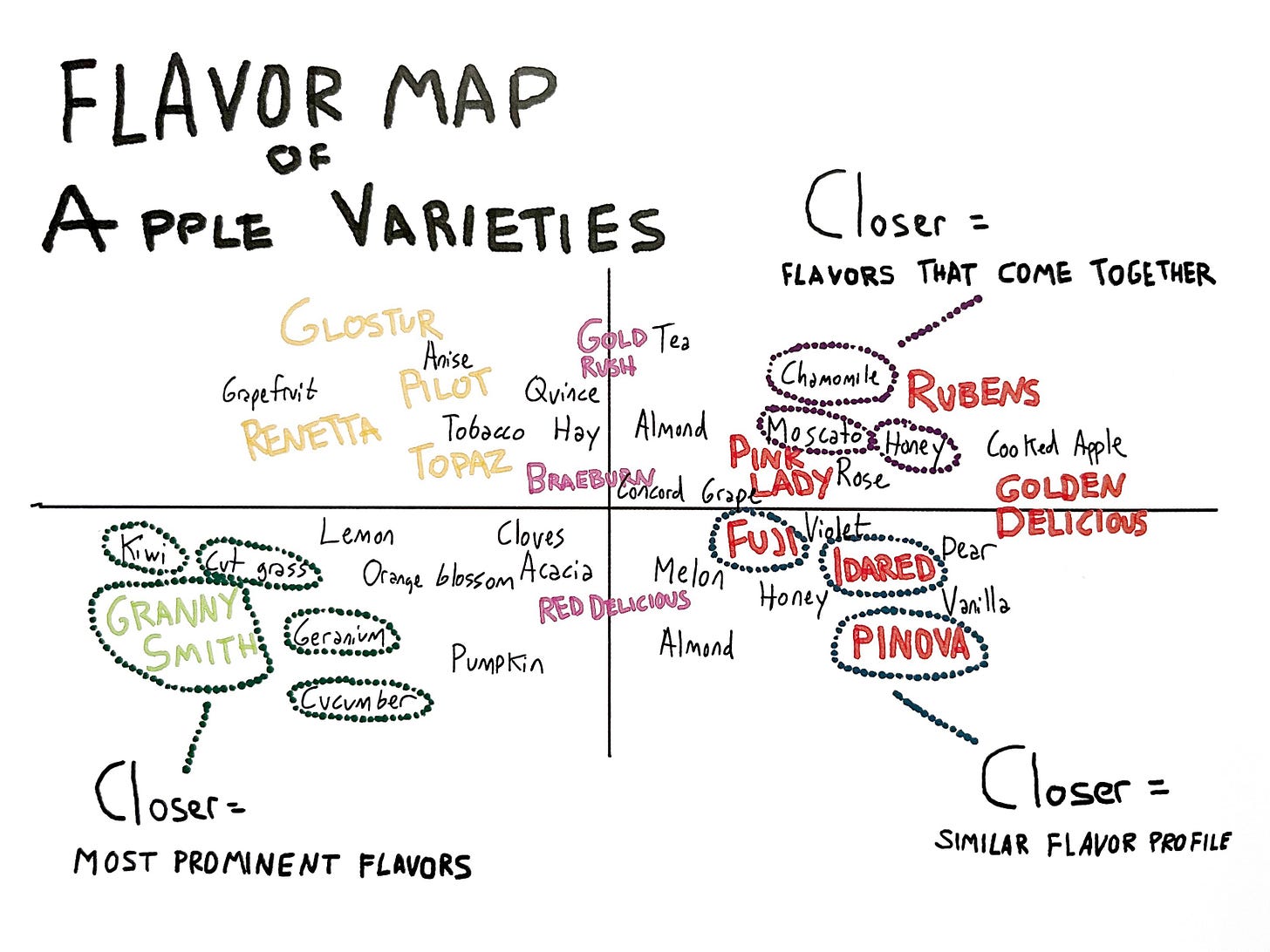

And further, “This is how certain groups of delicious things are related. And here’s some vocabulary to describe the ways in which they’re delicious and how similar-tasting delicious things differ from each other.”

Dr. Johnson is a flavor scientist and the science director for Noma Projects as well as the founder of a flavor consultancy. “Flavor is molecules,” she announces on the very first page of the book. “Tiny amounts of matter make up everything you can taste or smell.”

But you don’t have to be a chemistry whiz to read this book; in fact, it’s aimed at those who aren’t. As she said last month in a conversation with Alton Brown (she’s the science officer on his show Good Eats): When she’s talking about flavor with professional chefs, she finds it’s sometimes a challenge to convey the science of flavor to them, and she wished there was a book to point them to for reference. So she decided to write that very book, with the intention of demystifying the science behind flavor.

Molecules aside, she provides specific instructions on teaching yourself how to taste, and how to describe what you’re tasting. And yes, it’s something that many of us have to be taught. There’s an entire chapter on it early on in the book, with additional tips scattered throughout the rest of the text.

For instance, regarding fruit, she instructs:

When you taste a piece of fruit, here are some useful things to think about:

On top of general “fruitiness,” sweetness, and sourness, what dimensions of fruity complexity do you notice?

Is it fruity and crisp? Fruity and rich?

Does the fruitiness have a piercing or assertive quality to it, or is it softer and more blanketing?

What wispy or fleeting top notes can you sense? Below those, what are its deeper base notes like?

Do you get a honeyed quality or a sense of jamminess? Is it winey? Creamy? Musky? Can you notice any spiced, herbal, or floral qualities? Elements of these combine in different ways for different fruits: green-and-creamy honeydew vs. richly juicy-creamy peaches, deep and spiced cherry vs. deep and floral raspberry. Juicy and softly refreshing orange vs. juicy and piercing passion fruit.

If you like, you can then read about the molecules that are responsible for each quality. Or you can skip that and go straight to the descriptions of various fruit flavor families, and read her suggestions on how and when and why to use each one.

I should add that she illustrated the book herself.

Interspersed throughout are block-text asides with helpful tips. For example, the list “Easy Sour Additions to Make Your Life More Delicious” from the chapter on sour flavors includes (among other suggestions):

Buy tinned anchovies. Open the tin and squeeze lemon juice on the anchovies. Wait five minutes for the lemon to soak in a little, then eat the lemony anchovies on buttered bread.

Sprinkle a little sumac or black lime powder on roasted or poached foods (cauliflower, sweet potatoes, eggs, chicken, white fish, salmon, carrots, broccoli) right before you serve them.

Plop a spoonful of plain, whole-milk yogurt on root vegetables, roasted chicken, green beans, rice, and grilled lamb, as a sauce.

Or see one of her “Try This” tips: “Salts are soluble in water but poorly soluble in alcohol and oil, so it’s much easier to make a salty broth or boiling liquid than a salty oil or a salty liqueur. But you can also use this rule to your advantage: If you oil something and then sprinkle it with salt, the oil film prevents the salt from mixing with water and dissolving, creating crunchy pops of salt for a little excitement. Try drizzling leaves like arugula or tender radicchio with olive oil before sprinkling sea salt on them. They’ll stay plumper and less wilted, and you’ll taste a lively saltiness.”

My homemade salads will be a little more delicious going forward.

Speaking of, the book’s cover boasts of “99 Recipes!” (exclamation point the book’s), although I stand by my initial statement that this is not a cookbook. The recipes are almost incidental to the book’s other information and its more holistic approach to flavor and deliciousness and spicing up your life in the most literal of ways.

Some of these recipes are so simple they seem obvious, yet you’ve almost certainly never tried doing them yourself: Sprinkle some MSG on sliced cucumbers; “Eat with your hands,” Dr. Johnson specifically instructs. Others are more complex, for instance a walnut-and-amaro cake, which illustrates the use of other flavors to “chaperone” bitter ones.

Some reveal how to make your favorite dishes even more delicious, like the recipe for Umami-Boosted Cacio e Pepe. Others tell how to make things you perhaps didn’t know you could make yourself, such as crème fraiche. (Glory be, an item not available within at least a two-mile radius of my apartment is now something I can ferment in my own fridge.)

Still others swap out ingredients assumed mandatory for unexpected ones. Try using cilantro as a base for pesto instead of the customary basil, she suggests. Or see the recipe for Underappreciated Fragrant Spice Pumpkin Pie, which employs cardamom, korarima, cubeb peppercorns, and grains of paradise in place of the usual baking-spice favorites.

These ingredient swaps and other unexpected instructions don’t come out of nowhere. I often paraphrase a quote attributed to Picasso thusly: “You have to first know the rules so you can then break them effectively.” This book follows much the same mindset, explaining the rules—the laws and patterns of science and flavor—then suggesting science-informed ways of shattering your assumptions. You might never approach preparing a meal the same way again.