On the Hunt for Old Booze

Dusty bottles can be full of mysteries. So, too, is a new book about these coveted bottles and the people who pursue them.

Assuming you have even a passing familiarity with the current state of the drinks world, you’re no doubt aware that very old (or “dusty”) booze has become extremely covetable in the past decade or so. Bars, in New York City and elsewhere, have opened for the sole purpose of showcasing decades-old spirits. Bottles can sell for five figures (and up!) at auction. Collectors scramble to beat each other to a newly uncovered stash. It’s tempting to make a tulip-mania joke.

Some collectors like these old bottles merely for the investment they represent: Demand is growing exponentially, and these bottles are a finite resource, so they’re sure to keep skyrocketing in value. Some enjoy the historical aspect: holding, and perhaps drinking, an actual piece of history and being transported in time. Some covet these bottles because the liquid within them tastes significantly different from the spirits being produced today (“better” is a matter of opinion, but many would argue they’re better, too); they certainly don’t make ‘em like they used to, in the most literal sense.

I’m not a collector of these bottles myself. The closest to dusty-hunting I personally get is searching for liquor stores with bottles of recent-release Chartreuse languishing on their shelves at pre-pandemic prices. I’m not entirely uninterested in them, though.

Old booze is relatively hard to come by in NYC, and like seemingly everything else in this city, it commands a premium that puts it far out of my financial reach. But several years ago, within the space of a few months, I got to both experience a Fernet-Branca vertical tasting (the ‘80s are great; the Branca family scion is particularly fond of ’84) and attend the opening night of the NYC branch of dusty-focused bar The Office, when its owner was in a particularly festive and generous mood. Likely due to that good fortune, I acquired an appreciation for and curiosity about old liqueurs and amari.

On a brief trip to Chicago a couple years back, I visited the city’s old-booze meccas—Milk Bar, Billy Sunday, and the original location of The Office—where I tasted things like “bug juice” Campari from the ‘80s, Cynar from the ‘60s, Suze from the ‘50s, Benedictine from the ‘40s, and even had a Brooklyn cocktail made with Amer Picon from the ‘50s. “How on earth do you find these bottles?” I asked the beverage director at one spot.

I hadn’t realized what a loaded question I’d posed.

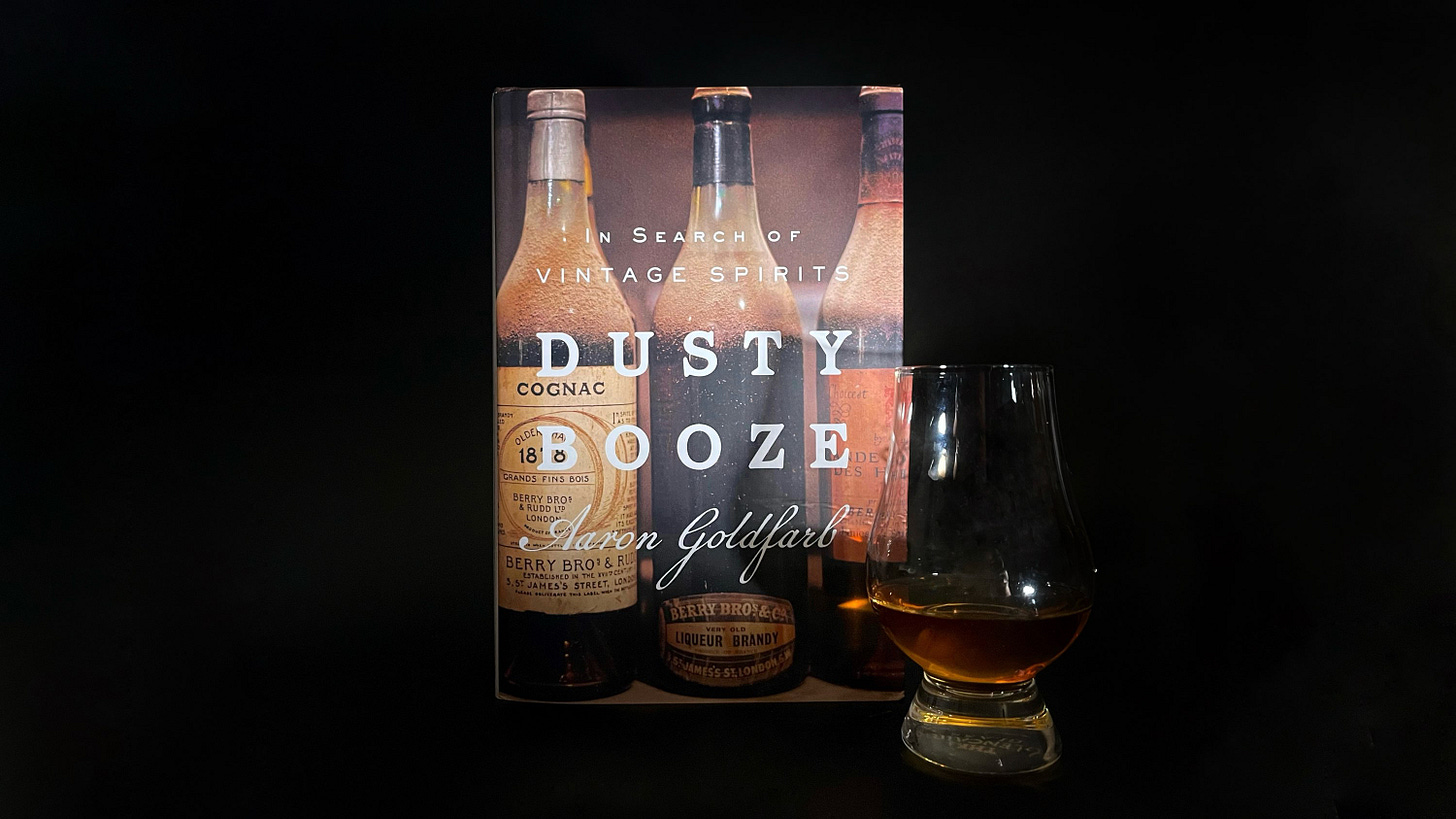

The lengths to which “dusty hunters” will go in order to acquire these rare and prized bottles—and to keep their sources secret from their fellow hunters—is the focus of a new book, Dusty Booze: In Search of Vintage Spirits, by the acclaimed drinks journalist Aaron Goldfarb.

My assumption, before cracking the book open, was that it would be chock-full of service information on these bottles: where to find them, highly valuable labels to look for, etc.

But from the very first page, it became clear that the reader is in for an even greater treat: the pleasure of accompanying Goldfarb as he falls down the strange rabbit hole into the world of dusty hunters, and meeting many of the odd characters who are driving the industry.

My favorite subgenre of narrative nonfiction can be summarized thusly: The author asking, of a subculture obsessed with an extremely niche interest, “Who are these weirdos, and what makes them tick?” and 200 pages later realizing “Oh no I’ve become one of them.” *

This book isn’t quite that—limitations of finances and free time keep its author from entirely following in his subjects’ footsteps—but you sense he’s hovering on the edge as he immerses himself in the details of dusty-hunting.

Driving the book are the stories of several prominent “dusty hunters” and a central mystery: Who was the enormously important celebrity who had amassed “the most coveted liquor collection in Los Angeles?” And once the answer is revealed, more questions remain: Will the hunter we’re following eventually get his hands on it? Who’s competing with him to acquire it? And does the collection even still exist?

But if you’re simply looking to learn what to buy, or at least what to keep an eye out for and why, there’s plenty of that info, too, primarily in skimmable block form with titles like “Key Bourbon Dusties” and “How to Decipher and Date Old Bottles.” Goldfarb also explains why old booze may, in fact, be objectively more delicious than current-production stuff—think barrels made from older wood that impart greater flavor, and less oversight by conglomerates that prize efficiency over artistry, among other reasons.

Take the example of El Tesoro tequila, for instance. Goldfarb writes:

El Tesoro … is admittedly still pretty damn great today, still produced at La Altena Distillery in Arandas, still made by the Camarena family. But when it’s placed side by side with the stuff from the past, anyone can tell it’s simply not as good as it used to be.

So you have to ask why.

Most obvious is that a post-[Robert] Denton, Beam-Suntory acquisition increased the brand’s distribution footprint. Less obvious is what that means.

Denton sends me a YouTube link to a home-movie-quality video he made in 1992 in which [Denton’s partner Marilyn] Smith, with the help of Carlos Camarena, walks viewers through La Altena’s agave fields, distiller, bottling hall, and aging cellars.

“The purpose of the video was to educate distributor salespeople about this groundbreaking artisan tequila,” explains Denton. “It was literally made to travel back in time.”

Indeed, it’s a remarkable look into the recent past and an era of rustic, artisan craft that no longer exists.

We see agave field workers harvesting pinas (agave hearts) that are eight to twelve years old.

We see these hearts ground up by a tractor-pulled tahona (an enormous volcanic-stone wheel) while a barefoot worker, essentially in his underwear, shovels the ground-up agave fibers.

We see batador Don Pedro Coronado, shirtless, inside a small fermentation tank, the liquid up to his chest, breaking up the mash so it doesn’t form a cap.

We see a still that’s fueled by an 1870s-era locomotive boiler, loaded with the mash and distilled to exactly 80 proof—Marilyn sips some served to her in a cow’s horn.

We see a facility completely lacking in electricity, no different from how things were when it was founded by Don Felipe Camarena in 1937: everything done by hand, everything hauled around by hand or balanced atop one’s head.

“Tell me that El Tesoro production looks similar today under Beam-Suntory,” says [Kristopher] Peterson [of Mordecai, in Chicago], who also sends me a link, to a Hollywood-quality video currently on El Tesoro’s glossy, modern website, and he jokes, “I sincerely doubt you’ll find Don Pedro Coronado’s successor partially submerged in a small wooden fermentation tank separating the tahona-ground agave fibers by hand.”

Instead, an older, more camera-comfortable Carlos Camarena proudly walks viewers through a drone-shot agave field, past stainless-steel tanks and Cleaver-Brooks boilers, through an orderly warehouse with barrels stacked to the sky.

“There are certain things like using the tahona that impart a very different taste than putting it through a metallic grinder,” says Denton. “But the metallic grinder to a Mexican proprietor was a sign of success.”

And that’s what makes it hard to fully lament the days when tequila tasted better. To that Mexican proprietor, doing backbreaking labor at a distillery without electricity, you’re never going to convince him to keep doing all these things just because it makes a “better” tequila preferred by a small subset of moneyed American tequila dorks.

So, yes, the amount of labor and effort that went into making spirits decades ago supports the argument that back then they were of objectively better quality, and thus more delicious, than most of the modern-production stuff. But that’s only one reason why these older bottles are so coveted.

“The top reason, the unspoken reason, the true reason I believe vintage spirits are so hot these days is that they allow us to revisit the past,” Goldfarb writes in the book’s prologue. “Vintage spirits are drinkable time capsules in the sense that once bottled, the liquid doesn’t really change. Find a bottle, and you can truly taste what some bygone bourbon would have tasted like in 1934, soon after Prohibition ended. Or try what Don Draper and Roger Sterling would have been sipping on Madison Avenue in the 1960s.”

Which is true, of course. But we tend to romanticize the past, and the most glamorous versions of yesteryear were only experienced by the most privileged people who lived through them. For the rest, including the people who actually made the spirits, life was perhaps not as carefree as we like to imagine. It’s a good thing to remember when obtaining and drinking older bottles, and it means that these bottles perhaps really do deserve the high value assigned to them—not just for their age and history, but for the degree of labor that went into creating the liquid within.

May we all keep that in mind if we’re lucky enough to get to enjoy them.

—

*My very favorite example is The Wild Trees by Richard Preston. Everyone I’ve recommended this book to so far has thanked me after reading it. “I wish there was a sequel,” one friend told me.

The Sidecar:

For avid readers (and drinkers), the notion of talking with your favorite drinks-book author over cocktails and getting them to sign your copy of their newest book sounds like a dream. But that’s exactly what the Porchlight Book Club Series offers: With your ticket to the event (generally about $100) held at Porchlight, in Manhattan, you get a copy of the book, cocktails from a specially selected menu, and the chance to talk with the author. Recent authors have included Robert Simonson and Amanda Schuster; upcoming events will be announced on the bar’s website.

In other new-book news, I just got my hands on a copy of Flavorama, by noted food scientist Arielle Johnson, the science director at Noma Projects. This book has everyone in the food and drink world buzzing, and I can’t wait to dive in. More to come, if it’s as good as I expect.