The Spirits World Has Something to Learn from the Fashion and Travel Industries

And one master distiller knows it.

I experienced an extraordinary evening earlier this week, courtesy of the Sazerac Company and, in particular, Weller.

A bunch of us writers, plus some retail folks, et al, were ferried up to Blue Hill at Stone Barns and treated to a tasting and dinner at the renowned restaurant in celebration of the launch of Weller’s newest product, Weller Millennium. (It was delicious, yes, and at $7,500 per bottle, I don’t expect I’ll ever get the chance to sip it again even if I encounter it on the back bar at Jack Rose or any of the other serious whiskey bars for which I’m told most of the bottles are destined.)

While it was an extraordinary event, the thing I can’t stop thinking about was something a fellow drinks writer, Lincoln Chinnery, had said to me the evening before:

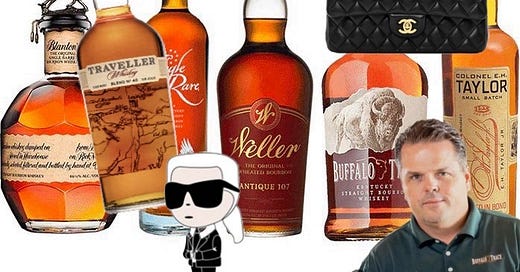

“Harlen Wheatley is kind of the Karl Lagerfeld of the spirits world.”

Even if you don’t recognize Wheatley’s name, you’re surely familiar with his work. He’s the prolific longtime master distiller at Buffalo Trace Distillery, which produces not just Buffalo Trace but also Blanton’s and Eagle Rare and the various Weller offerings and Pappy van Winkle. To name but a few.

I can’t think of any other master distiller in any spirits category who creates so many different products at such an extremely wide range of price and accessibility.

It was an offhand quip from Lincoln at a point in the night when we’d already had a few drinks. But it stuck in my brain, and the more I thought about it, the more accurate an analogy I realized it was.

Not many non-fashion folks are aware of the breadth of Lagerfeld’s contributions across his industry. He’s best known, of course, for being the personality driving Chanel. He spent decades as the creative director of both that brand and also of Fendi, successfully revitalizing both luxury brands, and he also created a much lower-priced label bearing his own name. By the time of his death in 2019 (at the age of 80-something; he was cagey about the actual year of his birth), he was producing, according to The New York Times, an average of 14 collections per year, not even including collaborations or special projects.

He was also the first designer to produce a collection for the fast-fashion retailer H&M—a move that ruffled plenty of fashion-industry feathers at the time, and which instituted lasting changes within the industry. The collaboration essentially singlehandedly smashed the divide between luxury and mass-market fashion. It also introduced the concepts of drops, designer collaborations, and more that we now take for granted 20 years later.

I struggle to think of another designer who has been not only so prolific, but also so willing to span luxury and mass-market and to such extremes. And in doing so, Lagerfeld became a household name even to those who’ve never picked up a copy of Vogue. He arguably left a greater legacy than any designer since Coco Chanel herself.

A strong case can be made that Wheatley is doing exactly the same within the spirits world—in fact, I think you can draw precise parallels aplenty between the two men’s ideals and outputs. Both men share a respect for relatively accessible price points: Dresses from the line bearing Lagerfeld’s name rarely retail for more than $200 (although I’ve seen them in vintage stores for twice that). Pappy, despite its astronomical resale prices, has an MSRP of $300 per bottle for its 23-year-old expression. Wheatley’s Experimental Collection can, perhaps, be viewed similarly to fashion’s runway garments: one-off proof-of-concept offerings. Right down to both men’s mass-market collaborations that had/have everyone in their respective industries questioning the sanity of their respective decisions. (And so on and so forth; I came up with a long mental list of parallels for my own amusement, but I’ll spare you that.)

A few months ago, Wheatley came out with Traveller Whiskey, created in collaboration with country musician Chris Stapleton and retailing for $40 a bottle.

Spirits-industry insiders were nonplussed. Why on earth would the maker of Pappy lower himself to making a cheap whiskey that, frankly, most reviewers didn’t like? Whispers abounded about cannibalization of Buffalo Trace’s similarly priced flagship offering or even brand dilution. Traveller showed none of the sophistication of Buffalo Trace’s other bottles. It was the whiskey equivalent of switching from silk to polyester.

But what these insiders had overlooked was that, unlike many new whiskey releases, this product wasn’t for us. It was designed with an entirely different audience in mind: those new to the whiskey category, switching over from beer or whatnot. And to appeal to those drinkers, this bottle had to be accessible in terms of both price and flavor—meaning that its lack of appeal to whiskey sophisticates is by design. Andrew Duncan, the global brand director for American whiskey at Sazerac, confirmed as much to me over dinner at Stone Barns. And it’s working: The new product is selling like crazy in the middle of the country, he says.

Once Traveller drinkers are comfortable with that bottle, it’s expected they’ll make the move up to the more “prestigious” Buffalo Trace at some point. And once they spend a few years with that, palate and budget permitting, ideally they’ll move on to the Weller offerings.

Which is to say, the inexpensive, unsophisticated Traveller is a way to draw people into both the category and the company—which is set up to then keep them there. Brand loyalty is perhaps underappreciated by casual consumers. Did you grow up drinking Coke or Pepsi? Which one do you drink now?

“Most people drink out of fear,” drinks writer Noah Rothbaum stated during a whiskey panel discussion earlier this week. He elaborated that most people choose their drinks out of a form of societal or peer pressure, drinking what their dad, or boss, or best friend drinks.

Those without a personal role-model whiskey drinker, the Sazerac Company hopes, perhaps will drink what their favorite musical artist purportedly had a hand in creating. And if they like it, they’ll stick with it.

No matter what point at which a drinker enters the Buffalo Trace Distillery’s various offerings, there’s room to move up as their preferences evolve.

It’s a strategy the travel industry has employed for decades. The most obvious example, I suppose, would be the increasing stratification of each airline: You’ve got first class (and, at some airlines, products superior to even first), business, premium economy, economy, the relatively new basic economy, and partnerships with regional airlines for small puddle-jumper flights. Ever pass by those cushy lie-flat business-class seats while walking to your cramped one at the back of the plane and think, “Yeah, whenever I can manage it, I’m gonna splurge and fly business class one of these days”? That’s the idea.

But I think an even better example might be hotel chains. Because whether or not you realize it, most hotels are indeed owned by some major conglomerate, whether it be Marriott or IHG or whatnot. Let’s take Hilton as an example. Twenty-two separate hotel brands exist under the Hilton umbrella, from the luxury Waldorf-Astoria properties to the “boutique” offerings of the Curio and Tapestry collections, right down to the airport-adjacent economy-priced Hilton Garden Inns.

Frequenters of Conrad properties aren’t bothered by the association with Hilton Garden Inns; they perhaps aren’t even aware they exist. But if you grow up taking family vacations in family-friendly Doubletree hotels, reading room literature about Hilton’s higher-end offerings, maybe what seemed aspirational at the time is what you stay in once you grow up and have a job and your own disposable income for travel. That’s what the hotel industry is banking on, in any case.

Why aren’t more spirits companies taking a cue from Buffalo Trace and addressing a wider market range, expanding “downward” as well as up? Plenty offer expensive new products or limited-edition bottlings, but rarely do we see a new more mass-market offering hit liquor-store shelves. My guess is there’s a certain degree of snobbery involved, of not wanting to be associated with a less-premium product than their flagship offering. But I’d argue that expanding to include a wider audience is good business. Exposing more people to a brand can only work in the brand’s favor.

A rising tide of drinkers lifts all boats. But if you can get those drinkers on your brand’s boat right from the start and then keep them on there as their preferences evolve, surely that’s an even bigger win.

OMG. So nice to be quoted. The parallels between the worlds of fashion and Spirits are made clear here and are presented with accurate and stunning details. Kathryn's piece contains sleek lines that leave little to the imagination, revealing something we all should be paying attention to...much like a little black dress by Nicole Miller. Attention getting, thought provoking, and well made. Bravo!